For the average person looking to navigate the city of Chicago, there is a common piece of advice shared, “follow the grid!” Known as one of the most orderly and consistent street designs in the world, it is a source of pride as well as ease for visitors and residents.

For scientists and researchers within the U.S. Department of Energy’s Community Research on Climate and Urban Science (CROCUS), though, Chicago’s grid system is ground zero for a whole host of inequities related to the impacts of climate change.

Max Berkelhammer recently dove deeper into this during a panel discussion with the Association for Health Care Journalists. He serves as Associate Professor of Earth and Environmental Sciences at University of Illinois Chicago and co-Lead Institutional PI for CROCUS. He was joined by fellow panelist Lori Burns, flooding activist and Greater Chatham Initiative (GCI) volunteer. GCI is a CROCUS partner. Cyatharine Alias, Manager of Community Infrastructure & Resilience with the Center for Neighborhood Technology, also took part in the discussion.

A critical aspect of Berkelhammer’s work is understanding climate change at a hyper-local scale – a scale necessary to address climate change impacts in cities.

“Traditional climate models are effective at predicting large-scale patterns, but these models cannot accurately or universally capture the details of a city’s climate. Through the work of CROCUS, we will be able to understand not just by neighborhood but really block-by-block how residents are impacted by climate change,” he said.

Focusing particularly on flooding, Berkelhammer explained that city neighborhoods differ vastly in terms of how much water they can absorb or channel away. Concrete, sewers, parks, trees, and even Chicago’s grid-system of streets play a part in determining which areas will flood. Therefore, by collaborating directly with residents to study man-made problems and the environmental elements, researchers can work to find the best solutions for each area.

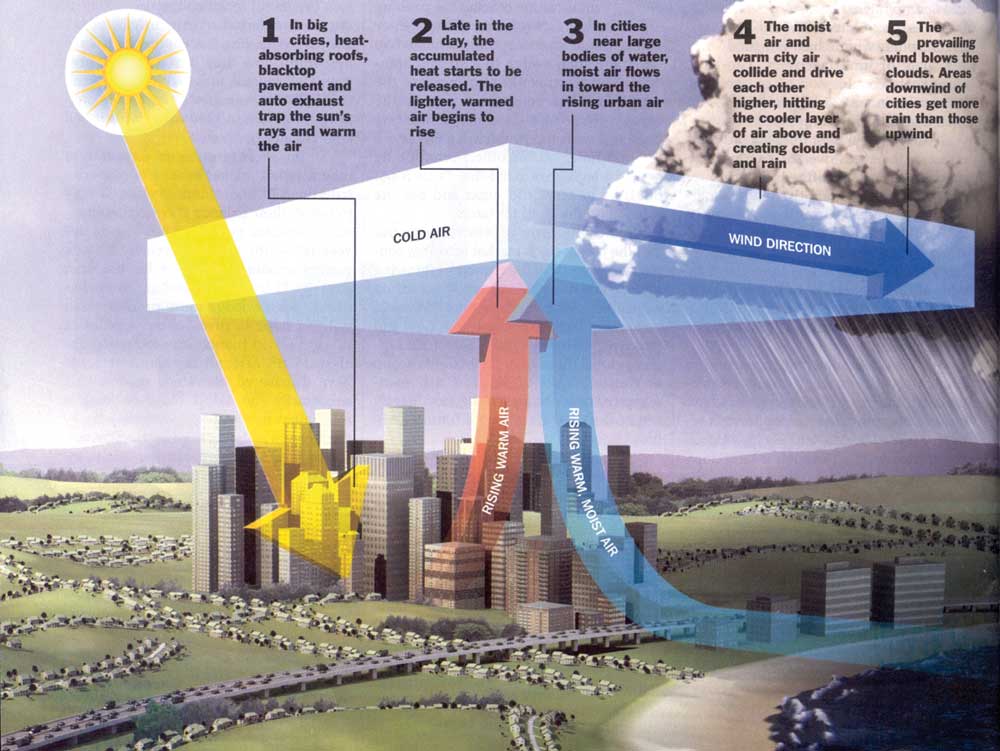

And this is critical, as issues with flooding are only expected to intensify – particularly for cities like Chicago, where extreme rain is enhanced by the interplay between the built and natural environments. ( see graphic).

“Many people don’t realize but Chicago was actually built on a swamp. When you combine that with the fact that the Great Lakes are rising, that rain storms have higher intensities and the installation of more impermeable surfaces like concrete, it is only going to cause more issues,” Berkelhammer said.